Animals

In Book II of The Sugar-Cane, James Grainger describes various Caribbean animals, including monkeys, rats, and insects, which are portrayed as having the ability to damage or destroy cane and hence the planter’s livelihood. While these animals posed real threats to crops, Grainger may also have meant these parts of the poem to possess symbolic meaning. During the eighteenth century, emblematic modes of natural history that endowed animals and other natural elements with extra-scientific significance were still popular. Thus, for example, an account of a fox could contain not only a physical description of the animal but also stories that associated it with slyness and cunning.

When reading the below passages, pay special attention to the language that Grainger uses to describe animals. Why does he describe insects as belonging to an “insect-tribe” (156) or even a “republic” (229)? Why does he describe monkeys as belonging to a “monkey-nation” (35)? These are political terms usually employed to describe groups of human beings: is Grainger comparing animals to human beings? If so, why might Grainger be doing this?

Note: For a more in-depth look at the tradition of emblematic natural history, please consult William B. Ashworth’s “Emblematic Natural History.” For further analysis of the depiction of insects in The Sugar-Cane, see Monique Allewaert’s “Insect Poetics: James Grainger, Personification, and Enlightenments Not Taken.”

—Stephen Fragano

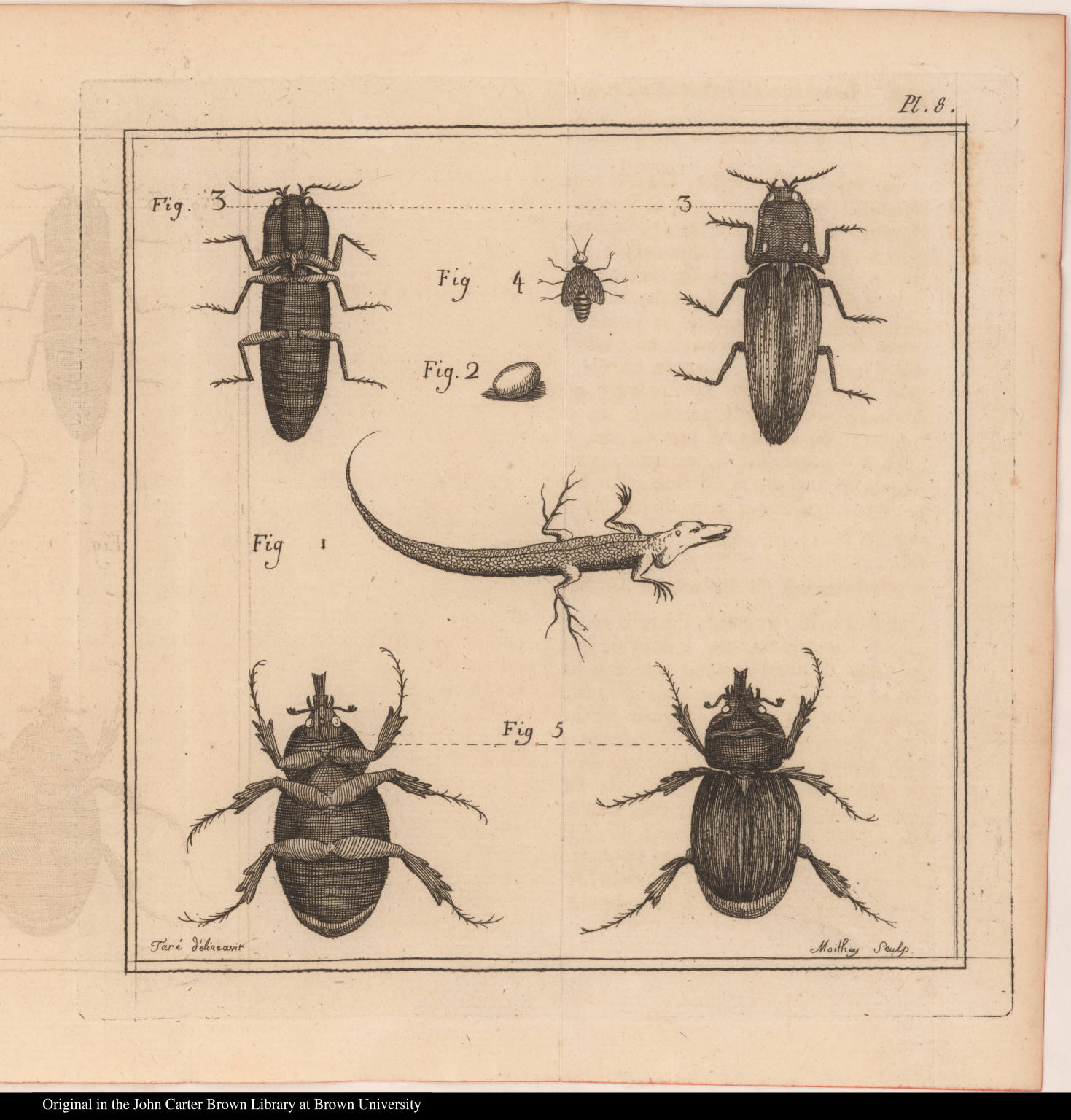

Illustrations of insects from Saint-Domingue (Haiti), engraved plate from Père Nicolson, Essai sur l’histoire naturelle de l’isle de Saint-Domingue, Paris, 1776, following p. 352.

Illustrations of insects from Saint-Domingue (Haiti), engraved plate from Père Nicolson, Essai sur l’histoire naturelle de l’isle de Saint-Domingue, Paris, 1776, following p. 352.

- "O WERE my pipe as soft, my dittied song"1

- As smooth as thine, my too too distant friend, [30]

- SHENSTONE;2 my soft pipe, and my dittied song

- Should hush the hurricanes tremendous roar,

- And from each evil guard the ripening Cane!

- DESTRUCTIVE, on the upland sugar-groves

- The monkey-nation3 preys: from rocky heights, [35]

- In silent parties, they descend by night,

- And posting watchful sentinels, to warn

- When hostile steps approach; with gambols,4 they

- Pour o’er the Cane-grove. Luckless he to whom

- That land pertains! in evil hour, perhaps, [40]

- And thoughtless of to-morrow, on a die

- He hazards millions; or, perhaps, reclines

- On Luxury’s soft lap, the pest of wealth;

- And, inconsiderate, deems his Indian crops5

-

Will amply her insatiate wants supply.6 [45]

- FROM these insidious droles7 (peculiar pest

- Of Liamuiga’s8 hills) would’st thou defend

- Thy waving wealth; in traps put not thy trust,

- However baited: Treble every watch,

- And well with arms provide them; faithful dogs, [50]

- Of nose sagacious, on their footsteps wait.

VER. 46. peculiar pest] The monkeys which are now so numerous in the mountainous parts of St. Christopher,9 were brought thither by the French when they possessed half that island. This circumstance we learn from Pere Labat,10 who farther tells us, that they are a most delicate food. The English-Negroes are very fond of them, but the White-inhabitants do not eat them. They do a great deal of mischief in St. Kitts, destroying many thousand pounds Sterling’s worth of Canes every year.

- With these attack the predatory bands;

- Quickly the unequal conflict they decline,

- And, chattering, fling their ill-got spoils away.

- So when, of late, innumerous Gallic hosts11 [55]

- Fierce, wanton, cruel, did by stealth invade

- The peaceable American’s domains,

- While desolation mark’d their faithless rout;

- No sooner Albion’s12 martial sons advanc’d,

- Than the gay dastards to their forests fled, [60]

-

And left their spoils and tomahawks behind.

- NOR with less waste the whisker’d vermine-race,13

-

A countless clan, despoil the low-land Cane.

- THESE to destroy, while commerce hoists the sail,

- Loose rocks abound, or tangling bushes bloom, [65]

- What Planter knows?—Yet prudence may reduce.

- Encourage then the breed of savage cats…

VER. 64. These to destroy] Rats, &c. are not natives of America, but came by shipping from Europe. They breed in the ground, under loose rocks and bushes. Durante, a Roman, who was physician to Pope Sixtus Quintus,14 and who wrote a Latin poem on the preservation of health, enumerates domestic rats among animals that may be eaten with safety. But if these are wholesome, cane-rats must be much more delicate, as well as more nourishing. Accordingly we find most field Negroes fond of them, and I have heard that straps of cane-rats are publicly sold in the markets of Jamaica.15

- STILL other maladies infest the Cane, [155]

- And worse to be subdu’d. The insect-tribe16

- That, fluttering, spread their pinions to the sun,

- Recal the muse: nor shall their many eyes,

- Tho’ edg’d with gold, their many-colour’d down,

- From Death preserve them. In what distant clime, [160]

- In what recesses are the plunderers hatch’d?

- Say, are they wasted in the living gale,

- From distant islands? Thus, the locust-breed,

- In winged caravans, that blot the sky,

- Descend from far, and, ere bright morning dawn,

- Astonish’d Afric sees her crop devour’d. [165]

- Or, doth the Cane a proper nest afford,

- And food adapted to the yellow fly?17——

- The skill’d in Nature’s mystic lore observe,

- Each tree, each plant, that drinks the golden day, [170]

- Some reptile life sustains: Thus cochinille18

- Feeds on the Indian fig;19 and, should it harm

- The foster plant, its worth that harm repays:

- But YE, base insects! no bright scarlet yield,

- To deck the British Wolf;20 who now, perhaps, [175]

- (So Heaven and George21 ordain) in triumph mounts

- Some strong-built fortress, won from haughty Gaul!22

- And tho’ no plant such luscious nectar yields,

- As yields the Cane-plant; yet, vile paricides!23

-

Ungrateful ye! the Parent-cane destroy. [180]

- MUSE! say, what remedy hath skill devis’d

- To quell this noxious foe? Thy Blacks send forth,

- A strong detachment! ere the encreasing pest

- Have made too firm a lodgment; and, with care,

- Wipe every tainted blade, and liberal lave [185]

- With sacred Neptune’s purifying stream.

- But this Augaean toil24 long time demands,

- Which thou to more advantage may’st employ:

- If vows for rain thou ever did’st prefer,

VER. 171. Thus cochinille] This is a Spanish word. For the manner of propagating this useful insect, see Sir Hans Sloane’s Natural History of Jamaica.25 It was long believed in Europe to be a seed, or vegetable production. The botanical name of the plant on which the cochinille feeds, is Opuntia maxima, folio oblongo, majore, spinulis obtusis, mollibus et innocentibus obsito, flore, striis rubris variegato. Sloane.

- Planter, prefer them now: the rattling shower, [190]

- Pour’d down in constant streams, for days and nights,

- Not only swells, with nectar sweet, thy Canes;

-

But, in the deluge, drowns thy plundering foe.

- WHEN may the planter idly fold his arms,

- And say, “My soul take rest?” Superior ills, [195]

- Ills which no care nor wisdom can avert,

- In black succession rise. Ye men of Kent,26

- When nipping Eurus,27 with the brutal force

- Of Boreas,28 join’d in ruffian league, assail

- Your ripen’d hop-grounds;29 tell me what you feel, [200]

- And pity the poor planter; when the blast,30

- Fell plague of Heaven! perdition of the isles!

- Attacks his waving gold. Tho’ well-manur’d;

- A richness tho’ thy fields from nature boast;

- Though seasons pour; this pestilence invades: [205]

- Too oft it seizes the glad infant-throng,

- Nor pities their green nonage:31 Their broad blades

- Of which the graceful wood-nymphs erst compos’d

- The greenest garlands to adorn their brows,

VER. 205. Tho’ seasons] Without a rainy season, the Sugar-cane could not be cultivated to any advantage: For what Pliny the Elder writes of another plant may be applied to this, Gaudet irriguis, et toto anno bibere amat.32

VER. 205. this pestilence] It must, however, be confessed, that the blast is less frequent in lands naturally rich, or such as are made so by well-rotted manure.

- First pallid, sickly, dry, and withered show; [210]

- Unseemly stains succeed; which, nearer viewed

- By microscopic arts, small eggs appear,

- Dire fraught with reptile-life; alas, too soon

- They burst their filmy jail, and crawl abroad,

- Bugs of uncommon shape; thrice hideous show! [215]

- Innumerous as the painted shells, that load

- The wave-worn margin of the Virgin-isles!

- Innumerous as the leaves the plumb-tree33 sheds,

- When, proud of her faecundity, she shows,

- Naked, her gold fruit to the God of noon. [220]

- Remorseless to its youth; what pity, say,

- Can the Cane’s age expect? In vain, its pith

- With juice nectarious flows; to pungent sour,

- Foe to the bowels, soon its nectar turns:

- Vain every joint a gemmy34 embryo bears, [225]

- Alternate rang’d; from these no filial young

- Shall grateful spring, to bless the planter’s eye.—

- With bugs confederate, in destructive league,

- The ants’ republic35 joins; a villain crew,

VER. 218. the plumb-tree sheds,] This is the Jamaica plumb-tree. When covered with fruit, it has no leaves upon it. The fruit is wholesome. In like manner, the panspan36 is destitute of foliage when covered with flowers. The latter is a species of jessamine, and grows as large as an apple-tree.

- As the waves, countless, that plough up the deep, [230]

- (Where Eurus reigns vicegerent37 of the sky,

- Whom Rhea38 bore to the bright God of day)

- When furious Auster39 dire commotions stirs:

- These wind, by subtle sap, their secret way,

- Pernicious pioneers! while those invest, [235]

- More firmly daring, in the face of Heaven,

-

And win, by regular approach, the Cane.

- ‘GAINST such ferocious, such unnumber’d bands,

-

What arts, what arms shall sage experience use?

- SOME bid the planter load the favouring gale, [240]

- With pitch, and sulphur’s suffocating steam:—

- Useless the vapour o’er the Cane-grove flies,

- In curling volumes lost; such feeble arms,

- To man tho’ fatal, not the blast subdue.

- Others again, and better their success, [245]

- Command their slaves each tainted blade to pick

- With care, and burn them in vindictive flames.

VER. 231. Eurus reigns] The East is the centre of the trade-wind in the West-Indies, which veers a few points to the North or South. What Homer40 says of the West-wind, in his islands of the blessed, may more aptly be applied to the trade-winds.

- Labour immense! and yet, if small the pest;

- If numerous, if industrious be thy gang;

- At length, thou may’st the victory obtain. [250]

- But, if the living taint be far diffus’d,

- Bootless41 this toil; nor will it then avail

- (Tho’ ashes lend their suffocating aid)

- To bare the broad roots, and the mining swarms

- Expose, remorseless, to the burning noon. [255]

- Ah! must then ruin desolate the plain?

- Must the lost planter other climes explore?

- Howe’er reluctant, let the hoe uproot

- The infected Cane-piece; and, with eager flames,

- The hostile myriads thou to embers turn: [260]

- Far better, thus, a mighty loss sustain,

- Which happier years and prudence may retrieve;

- Than risque thine all. As when an adverse storm,

- Impetuous, thunders on some luckless ship,

- From green St. Christopher, or Cathäy bound: [265]

- Each nautic art the reeling seamen try:

- The storm redoubles: death rides every wave:

- Down by the board the cracking masts they hew;

- And heave their precious cargo in the main….

VER. 265. Cathäy] An old name for China.

-

Gilmore identifies this quotation as an adaptation from Milton’s Comus (l.86). ↩︎

-

William Shenstone (1714-1763), English poet and famed innovator of landscape gardening, which he practiced on his estate, The Leasowes. Grainger enclosed a draft of The Sugar-Cane in a 5 June 1762 letter to his friend Bishop Thomas Percy, asking him and Shenstone to read and comment on it. He added that “The second book you will see is addressed to our friend at the Leasowes; and I must tell you it is my favourite of the whole” (Nichols 279). ↩︎

-

Monkeys are not indigenous to St. Kitts, but the vervet or African green monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops) had been introduced by the seventeenth century. Vervets most likely arrived in the Caribbean via slave ships from Africa. They quickly came to be considered pests because they established themselves in large numbers on the island and traveled around it in troops, raiding colonists’ crops. Today, the St. Kitts vervet population exceeds the human one, and vervets are still known for destroying farmers’ crops (and stealing tourists’ cocktails). Controversially, many of the vervets are now killed or trapped to serve in medical experiments. ↩︎

-

Leaps or capers, as made in dancing or playing. ↩︎

-

Sugar. ↩︎

-

Grainger warns that despite the fact that sugar plantations seem like sure investments with guaranteed profits, they nevertheless require expert knowledge and labor to succeed. ↩︎

-

Also droll, a buffoon or jester. ↩︎

-

Indigenous name for St. Kitts. ↩︎

-

The island of St. Christopher was known as Liamuiga by the indigenous Caribs who lived there. Columbus claimed it on behalf of Spain in 1493, and it was partitioned between the French and the English in the early seventeenth century, at which time it was primarily a tobacco colony. While the two countries exchanged control of the island several times during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was firmly under British control when Grainger left England in 1759 during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Grainger uses “St. Christopher,” “Liamuiga,” and “St. Kitts” interchangeably in the poem, but we have chosen to use “St. Kitts” on this site. St. Kitts has been part of the nation of St. Kitts and Nevis (also known as the Federation of St. Christopher and Nevis) since it gained independence from Great Britain in 1983. ↩︎

-

Jean Baptiste Labat (1663-1738), French missionary of the Dominican order who served as a priest and procurator in Martinique and Guadaloupe. Libertated the island of Martinique from British control in 1703. Later, a professor of philosophy and mathematics in Nancy, France, and author of the Nouveau voyage aux isles de l’Amerique (1722). ↩︎

-

Hostile French forces. Here, Grainger makes an analogy between the vervet monkeys and the French during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), the first truly global war that resulted in the establishment of Britain as the preeminent maritime and colonial power. ↩︎

-

Albion, a name of ancient Celtic origin for Britain or England. The term may also derive from the Latin word for white (albus) and refer to the white cliffs of Dover. ↩︎

-

Refers either to the black rat (Rattus rattus) or the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), two Old World species of rats that arrived in the Caribbean with colonization and are now considered invasive species. This line of the poem also relates to one of the most famous and perhaps apocryphal stories about the reception and publication of The Sugar-Cane. In his Life of Johnson, James Boswell recalls a reading of a manuscript draft of the poem that took place at the home of painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. The line, “Now, Muse, let’s sing of rats,” is supposed to have caused the audience to burst into laughter. In response, Grainger deleted the word “rats” from the poem and replaced it with “whisker’d vermine-race” (Irlam 390-391). ↩︎

-

Castore Durante da Gualdo (1529-1590), botanist and physician to the Popes Gregory XIII and Sixtus V. Author of Herbaria nuovo (1585) and Il tesoro della sanità (1586). ↩︎

-

Grainger may have been referring to a passage from Hans Sloane’s A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica (1707, 1725) that reads, “Rats are likewise sold by the dozen, and when they have been bred amongst the Sugar-Canes, are thought by some discerning people very delicious Victuals” (1.xx). Sloane seems to imply that all Jamaicans, and not just the enslaved, ate rats. ↩︎

-

Locusts, one of several species of acridids (family Acrididae) that are known for swarming and migrating and causing great damage to crops. ↩︎

-

May be Diachlorus ferrugatus, a small biting fly native to Central America and the southeastern United States. ↩︎

-

Refers to the cochineal insect (Dactylopius coccus), the source of a highly prized red dye. The cochineal insect is native to tropical and subtropical Mexico and South America and was used in those places in the precolonial era to dye textiles and other objects. ↩︎

-

Common name for cactus plants of the genus Opuntia, which contains over a hundred species that are distributed throughout the Americas. Some species of Opuntia served as food plants for the cochineal insect. Also known as nopal and commonly consumed by human beings as food. ↩︎

-

James Wolfe (1727-1759), English army officer. Like Grainger, he served in the Netherlands during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and during the Scottish Jacobite Rising of 1745. Appointed Major-General in North America in 1758, Wolfe is perhaps best known for defeating French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, marquis de Montcalm, and the French army on the Plains of Abraham outside of Quebec city in September 1759. Wolfe was fatally wounded during the battle, but his victory brought an end to the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). ↩︎

-

George III (1738-1820), king of Britain from 1760 to 1820. ↩︎

-

France. ↩︎

-

Father killer. Here, Grainger refers to parasites—and perhaps puns on the similarities between “paracide” and “parasite”—that kill the plants on which they feed (in this case, the sugarcane). Grainger may be referring to the sugarcane borer (Diatraea saccharalis), a moth native to South and Central America whose larvae bore holes in sugarcane plants and do great damage on plantations. ↩︎

-

Augeas, king of Elis, owned the stables that Hercules cleaned in the course of completing one of his twelve labors. Grainger is comparing the labor of washing every leaf in a cane field with the labors of Hercules, who cleaned the stables by redirecting the Alpheus and Peneus rivers through them. ↩︎

-

Hans Sloane (1660-1753) was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector who traveled to Jamaica in 1687 with Christopher Monck, second duke of Albemarle and newly appointed governor of Jamaica. During his stay in Jamaica, Sloane amassed an extensive collection of natural specimens, including plants, that later served as the basis for his natural history, A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica (1707, 1725). Sloane also succeeded Isaac Newton as president of the Royal Society in 1727. Upon his death, he bequeathed his extensive collections, which he had made considerable additions to after returning from Jamaica, to the British nation. These served as the founding collections of the British Museum, the British Library, and the Natural History Museum in London. Sloane discusses the propagation of cochineal in his Voyage (2.208). ↩︎

-

Kent is a county in southeastern England. ↩︎

-

In Greek mythology, the east wind. ↩︎

-

In Greek mythology, the north wind. ↩︎

-

According to Gilmore, Grainger refers in these lines to the arrival of the hop aphid or Damson hop aphid (Phorodon humuli) to Kentish hop fields. These flies traveled on the wind and caused great damage to crops. ↩︎

-

Gilmore identifies the blast as the disease that also has been called the black blight. It results from an infestation by the West Indian cane fly (Saccharosydne saccharivora). ↩︎

-

Period of immaturity. ↩︎

-

“It rejoices in watering, and it loves to drink the whole year round.” Adapted from Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, Book XIII, Chapter 7. The original line reads, “Gaudet riguis totoque anno bibere, cum amet sitientia.” ↩︎

-

According to Gilmore, Spondias purpurea. Its native range is Mexico to northern Colombia. ↩︎

-

Gem-like, brilliant, glittering. ↩︎

-

Ant colonies were often represented as model republics in early modern and eighteenth-century accounts because of their ability to work together for the collective good. For example, in his True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (1657), Richard Ligon observed that he once put a pot filled with sugar in the middle of a larger dish of water to see whether the ants would be able to find and retrieve the sugar. As he reported, the ants began venturing into the water even though they could not swim, so that their dead bodies could form a bridge for the others to use to access the sugar. The ants thereby “neglect[ed] their lives for the good of the publique” (64). ↩︎

-

According to Gilmore, the panspan or hog plum is Spondias mombin. Its native range is Mexico to the tropical Americas. ↩︎

-

In Greek mythology, the east wind. ↩︎

-

A person appointed by a king or other ruler to act in his place. ↩︎

-

Titan goddess who was the daughter of Gaia and the wife of her brother Kronos. The mother of the second generation of Greek gods, including Zeus, Hera, Demeter, Hades, Hestia, and Poseidon. ↩︎

-

Greek poet (8th-century BCE), author of the Iliad and the Odyssey. ↩︎

-

Useless, unprofitable. ↩︎