Indigenous Presence

Long before the arrival of European colonists, the Caribbean was home for millennia to Amerindians. Indeed, the Caribbean draws its name from the Carib peoples, and the poem notes indigenous names for specific islands throughout its verses. The Kalinago Caribs inhabited the Leeward and Windward Islands, while the Kalina Caribs resided in northern South America. The Arawaks, so named because of their language, also inhabited the Greater and Lesser Antilles and coastal South America, and, as a result, the Caribs and Arawaks often clashed over territorial rights. In spite of their conflicts, all of these groups relied upon and utilized the region’s natural resources: they cultivated crops for food and drink, and they learned which plants could be used as medicine or wielded as poison.

Faced with the task of describing various plants and reporting their possible uses, Grainger credits indigenous persons, whom he most often calls “Indians,” with this knowledge in several passages. Such moments appear primarily in Book I, but there are also mentions in the other three books, including a discussion of native plants within subsistence gardens at the poem’s close. These references, although limited in number, demonstrate the depth of Amerindian botanical and ecological knowledge. At the same time, Grainger relegates most mentions of indigenous peoples and knowledge in The Sugar-Cane to footnotes, structurally decentralizing indigenous authority within his text. Even Grainger’s use of the categories “Indian” and “indigenous” are fraught: he attaches such labels to inhabitants of both the East and West Indies, as well as to non-native plants that have merely grown in the region for a considerable period of time. This vagueness complicates tracing and locating specifically indigenous expertise. Moreover, Grainger appropriates indigenous knowledge for his own purposes in his preface to the poem, claiming that he has learned about “indigneous remedies” so thoroughly as to make his own “trials” of them. By arguing that such expertise and abilities should be “universally known,” Grainger further distributes this knowledge outside of indigenous communities, positioning his own text as the authoritative source of such information.

Despite Grainger’s attempts to simultaneously take possession of Amerindian knowledge and obscure its origins, we hope to allow the reader to recognize, explore, and meditate upon indigenous, rather than colonial, authority by collating the footnotes in which Grainger mentions indigenous peoples and the information he gained from them. Questions to consider include, How does Grainger characterize the relationship between indigenous and colonial inhabitants, and what exactly does he credit Amerindians with teaching him and other colonists? How does referring to indigenous peoples as “Indians” rather than “Carib,” “Kalinago,” or “Arawak” impact readers’ perceptions of such nations? Why does Grainger include indigenous words like “Liamuiga” and “suirsaak”? What effect does his frequent use of the passive voice have on our recognition of the origins and applications of plant knowledge?

Note: For a general overview of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, see the entries for “Arawaks,” “Caribs,” and “Taínos” in David Head’s Encyclopedia of the Atlantic World, 1400-1900. Hans Sloane’s A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica and Griffith Hughes’ The Natural History of Barbados provide further descriptions of plant usage by indigenous peoples.

—Kimberly Takahata

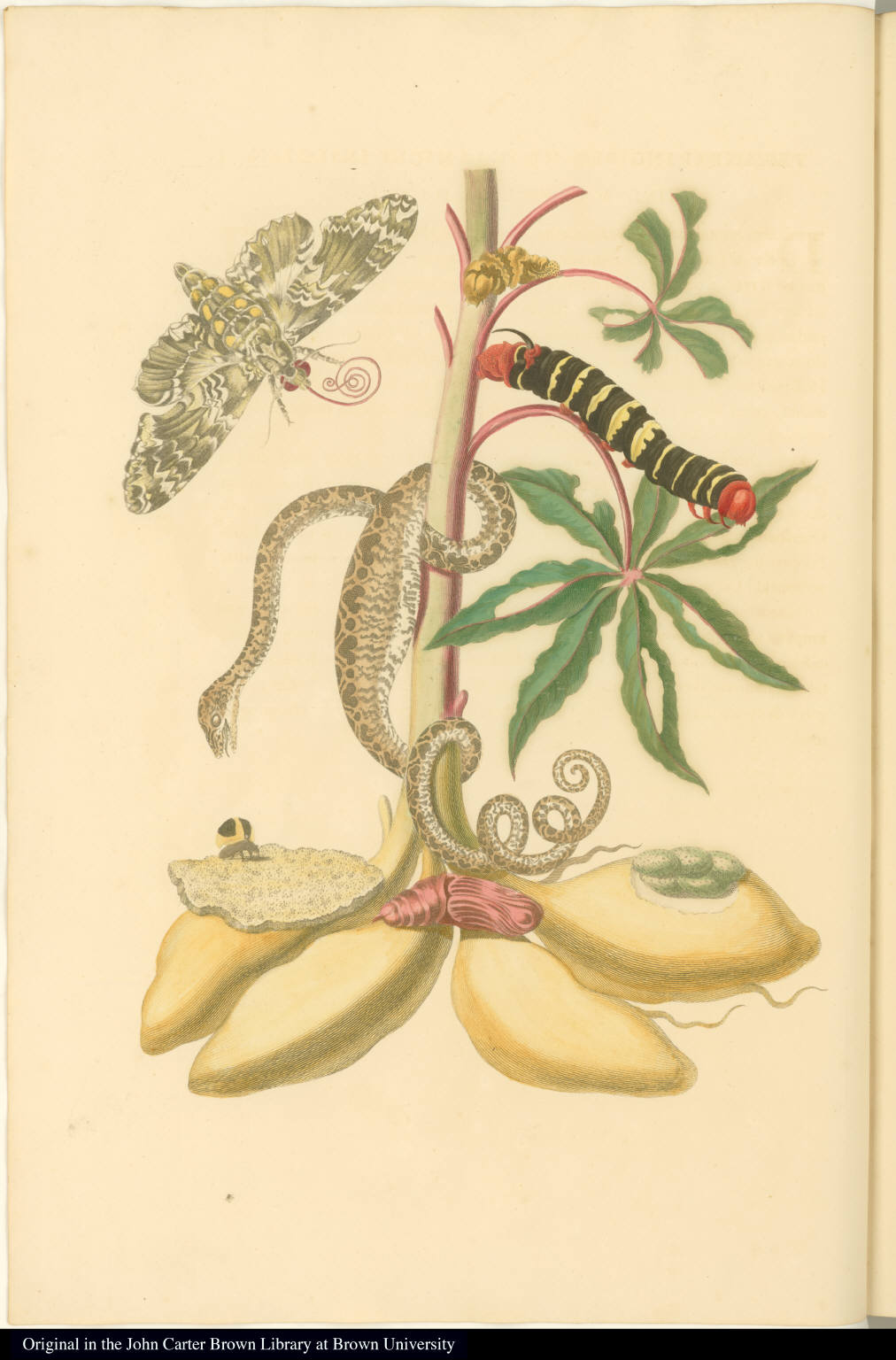

Cassava, hand-colored engraving from Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Amsterdam, 1719, pl. 5.

Cassava, hand-colored engraving from Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Amsterdam, 1719, pl. 5.

IN a West-India georgic,1 the mention of many indigenous remedies, as well as diseases, was unavoidable. The truth is, I have rather courted opportunities of this nature, than avoided them. Medicines of such amazing efficacy, as I have had occasion to make trials of in these islands, deserve to be universally known.2 And wherever, in the following poem, I recommend any such, I beg leave to be understood as a physician, and not as a poet….3

VER. 45. sabbaca:]4 This is the Indian name of the avocato, avocado, avigato, or, as the English corruptly call it, alligator-pear. The Spaniards in South-America name it aguacate, and under that name it is described by Ulloa.5 However, in Peru and Mexico, it is better known by the appellation of palta or palto. It is a sightly tree, of two species; the one bearing a green fruit, which is the most delicate, and the other a red, which is less esteemed, and grows chiefly in Mexico.6 When ripe, the skin peels easily off, and discovers a butyraceous,7 or rather a marrowy like substance, with greenish veins interspersed. Being eat with salt and pepper, or sugar and lime-juice, it is not only agreeable, but highly nourishing; hence Sir Hans Sloane8 used to stile it Vegetable marrow. The fruit is of the size and shape of the pear named Lady’s-thighs,9 and contains a large stone, from whence the tree is propagated. These trees bear fruit but once a year. Few strangers care for it; but, by use, soon become fond of it. The juice of the kernel marks linen with a violet-colour. Its wood is soft, and consequently of little use. The French call it Bois d’anise,10 and the tree Avocat: the botanical name is Persea….

VER. 60. green St. Christopher,]11 This beautiful and fertile island, and which, in Shakespear’s words, may justly be stiled

“A precious stone set in the silver sea,”12

lies in seventeenth degree N. L.13 It was discovered by the great Christopher Columbus,14 in his second voyage, 1493, who was so pleased with its appearance, that he honoured it with his Christian name. Though others pretend, that appellation was given it from an imaginary resemblance between a high mountain in its centre, now called Mount Misery, to the fabulous legend of the Devil’s carrying St. Christopher on his shoulders.15 But, be this as it will, the Spaniards soon after settled it, and lived in tolerable harmony with the natives for many years; and, as their fleets commonly called in there to and from America for provision and water, the settlers, no doubt, reaped some advantage from their situation. By Templeman’s Survey,16 it contains eighty square miles, and is about seventy miles in circumference. It is of an irregular oblong figure, and has a chain of mountains, that run South and North almost from the one end of it to the other, formerly covered with wood, but now the Cane-plantations reach almost to their summits, and extend all the way, down their easy declining sides, to the sea. From these mountains some rivers take their rise, which never dry up; and there are many others which, after rain, run into the sea, but which, at other times, are lost before they reach it. Hence, as this island consists of mountain-land and valley, it must always make a midling crop; for when the low grounds fail, the uplands supply that deficiency; and, when the mountain canes are lodged (or become watery from too much rain) those in the plains yield surprisingly. Nor are the plantations here only seasonable, their Sugar sells for more than the Sugar of any other of his Majesty’s islands; as

their produce cannot be refined to the best advantage, without a mixture of St. Kitts’ muscovado.17 In the barren part of the island, which runs out towards Nevis, are several ponds, which in dry weather crystallize into good salt; and below Mount Misery is a small Solfaterre and collection of fresh water, where fugitive Negroes often take shelter, and escape their pursuers.18 Not far below is a large plain which affords good pasture, water, and wood; and, if the approaches thereto were fortified, which might be done at a moderate expence, it would be rendered inaccessible. The English, repulsing the few natives and Spaniards, who opposed them, began to plant tobacco here A.D. 1623. Two years after, the French landed in St. Christopher on the same day that the English-settlers received a considerable reinforcement from their mother-country; and, the chiefs of both nations, being men of sound policy, entered into an agreement to divide the island between them: the French retaining both extremities, and the English possessing themselves of the middle parts of the island. Some time after both nations erected sugar-works, but there were more tobacco, indigo, coffee, and cotton-plantations, than Sugar ones, as these require a much greater fund to carry them on, than those other.19 All the planters, however, lived easy in their circumstances; for, though the Spaniards, who could not bear to be spectators of their thriving condition, did repossess themselves of the island, yet they were soon obliged to retire, and the colony succeeded better than ever. One reason for this was, that it had been agreed between the two nations, that they should here remain neutral whatever wars their mother-countries might wage against each other in Europe. This was a wise regulation for an infant settlement; but, when King James abdicated the British throne,20 the French suddenly rose, and drove out the unprepared English by force of arms. The French colonists of St. Christopher had soon reason, however, to repent their impolitic breach of faith; for the expelled planters, being assisted by their countrymen from the neighbouring isles, and supported by a formidable fleet, soon recovered, not only their lost plantations, but obliged the French totally to abandon the island. After the treaty of Ryswick,21 indeed, some few of those among them, who had not obtained settlements in Martinico22 and Hispaniola, returned to St. Christopher: but the war of partition soon after breaking out, they were finally expelled, and the whole island was ceded in Sovereignty to the crown of Great Britain, by the treaty of Utrecht.23 Since that time, St. Christopher has gradually improved, and it is now at the height of perfection. The Indian name of St. Christopher is Liamuiga, or the Fertile Island….

VER. 132. the bearded Fig]24 This wonderful tree, by the Indians called the Banian-tree; and by the botanists Ficus Indica, or Bengaliensis, is exactly described by Q. Curtius,25 and beautifully by Milton in the following lines:26

“The Fig-tree, not that kind renown’d for fruit,

“But such as at this day to Indians known,

“In Malabar and Decan spreads her arms;27

“Branching so broad and long, that in the ground,

“The bended twigs take root, and daughters grow

“About the mother-tree, a pillar’d shade,

“High over-arch’d, and echoing walks between.

“There oft the Indian herdsman, shunning heat,

“Shelters in cool, and tends his pasturing herds

“At Loop-holes cut through thickest shade.”——

What year the Spaniards first discovered Barbadoes is not certainly known; this however is certain, that they never settled there, but only made use of it as a stock-island….28

VER. 526. seen the humming bird,] The humming bird is called Picaflore by the Spaniards, on account of its hovering over flowers, and sucking their juices, without lacerating, or even so much as discomposing their petals.29 Its Indian name, says Ulloa, is Guinde, though it is also known by the appellation of Rabilargo and Lizongero. By the Caribbeans it was called Collobree. It is common in all the warm parts of America. There are various species of them, all exceeding small, beautiful and bold. The crested one, though not so frequent, is yet more beautiful than the others. It is chiefly to be found in the woody parts of the mountains. Edwards30 has described a very beautiful humming bird, with a long tail, which is a native of Surinam, but which I never saw in these islands. They are easily caught in rainy weather….

VER. 596. cassada,] Cassavi, cassava, is called Jatropha by botanists.31 Its meal makes a wholesome and well-tasted bread, although its juice be poisonous. There is a species of cassada which may be eat with safety, without expressing the juice; this the French call Camagnoc.32 The colour of its root is white, like a parsnip; that of the common kind is of a brownish red, before it is scraped. By coction the cassada-juice becomes an excellent sauce for fish; and the Indians prepare many wholesome dishes from it. I have given it internally mixed with flour without any bad consequences; it did not however produce any of the salutary effects I expected. A good starch is made from it. The stem is knotty, and, being cut into small junks and planted, young sprouts shoot up from each knob. Horses have been poisoned by eating its leaves. The French name it Manihot, Magnoc, and Manioc, and the Spaniards Mandiocha. It is pretended that all creatures but man eat the raw root of the cassada with impunity; and, when dried, that it is a sovereign antidote against venomous bites. A wholesome drink33 is prepared from this root by the Indians, Spaniards, and Portuguese, according to Pineda. There is one species of this plant which the Indians only use, and is by them called Baccacoua….34

VER. 598. to the soursop]35 The true Indian name of this tree is Suirsaak. It grows in the barrenest places to a considerable height. Its fruit will often weigh two pounds. Its skin is green, and somewhat prickly. The pulp is not disagreeable to the palate, being cool, and having its sweetness tempered with some degree of an acid. It is one of the Anonas, as are also the custard, star, and sugar-apples.36 The leaves of the soursop are very shining and green. The fruit is wholesome, but seldom admitted to the tables of the elegant. The seeds are dispersed through the pulp like the guava. It has a peculiar flavour. It grows in the East as well as the West-Indies. The botanical name is Guanabanus. The French call it Petit Corosol, or Coeur de Boeuf, to which the fruit bears a resemblance. The root, being reduced to a powder, and snuffed up the nose, produces the same effect as tobacco. Taken by the mouth, the Indians pretend it is a specific in the epilepsy.

VER. 605. cacao-walk]37 It is also called Cocao and Cocô. It is a native of some of

the provinces of South America, and a drink made from it was the common food of the Indians before the Spaniards came among them, who were some time in those countries ere they could be prevailed upon to taste it; and it must be confessed, that the Indian chocolate had not a tempting aspect; yet I much doubt whether the Europeans have greatly improved its wholesomeness, by the addition of vanellas and other hot ingredients.38 The tree often grows fifteen or twenty feet high, and is streight and handsome. The pods, which seldom contain less than thirty nuts of the size of a slatted olive,39 grow upon the stem and principal branches. The tree loves a moist, rich and shaded soil: Hence those who plant cacao-walks, sometimes screen them by a hardier tree, which the Spaniards aptly term Madre de Cacao.40 They may be planted fifteen or twenty feet distant, though some advise to plant them much nearer, and perhaps wisely; for it is an easy matter to thin them, when they are past the danger of being destroyed by dry weather, &c. Some recommend planting cassada, or bananas, in the intervals, when the cacao-trees are young, to destroy weeds, from which the walk cannot be kept too free. It is generally three years before they produce good pods;41 but, in six years, they are in highest perfection. The pods are commonly of the size and shape of a large cucumber.42 There are three or four sorts of cacao, which differ from one another in the colour and goodness of their nuts.43 That from the Caraccas is certainly the best. None of the species grow in Peru. Its alimentary, as well as physical properties, are sufficiently known. This word is Indian….44

VER. 438. the bending coco’s]45 The coco-nut tree is of the palm genus; there are several species of them, which grow naturally in the Torrid Zone.46 The coco-nut tree is, by no means, so useful as travellers have represented it. The wood is of little or no service, being spungy, and the brown covering of the nuts is of too rough a texture to serve as apparel. The shell of the nut receives a good polish; and, having a handle put to it, is commonly used to drink water out of. The milk, or water of the nut, is cooling and pleasant; but, if drunk too freely, will frequently occasion a pain in the stomach. A salutary oil may be extracted from the kernel; which, if old, and eaten too plentifully, is apt to produce a shortness of breathing. A species of arrack47 is made from this tree, in the East-Indies. The largest coco-nut trees grow on the banks of the river Oronoko.48 They thrive best near the sea, and look beautiful at a distance. They afford no great shade. Ripe nuts have been produced from them in three years after planting. The nuts should be macerated in water, before they are put in the ground. Coco is an Indian name; the Spaniards call it also palma de las Indias; as the smallest kind, whose nuts are less than walnuts, is termed by them Coquillo. This grows in Chili,49 and the nuts are esteemed more delicate than those of a larger size. In the Maldivy Islands,50 it is pretended, they not only build houses of the coco-nut tree, but also vessels, with all their rigging; nay, and load them too with wine, oil, vinegar, black sugar,51 fruit, and strong water,52 from the same tree. If this be true, the Maldivian coco-nut trees must differ widely from those that grow in the West-Indies. The coco53 must not be confounded with the coco-nut tree. That shrub grows in the hottest and moistest vales of the Andes. Its leaf, which is gathered two or three times a year, is much coveted by the natives of South-America, who will travel great journeys upon a single handful of the leaves, which they do not swallow, but only chew. It is of an unpleasant taste, but, by use, soon grows agreeable. Some authors have also confounded the coco-nut palm, with the coco, or chocolate-tree. The French call the coco-nut tree, Cocotier. Its stem, which is very lofty, is always bent; for which reason it looks better in an orchard than in a regular garden. As one limb fades, another shoots up in the center, like a pike. The botanical name is Palma indica, coccifera, angulosa….

VER. 282. Karukera] The Indian name of Guadaloupe.

VER. 283. Matanina] The Caribbean name of Martinico. The Havannah54 had not then been taken….

VER. 350. For taste, for colour, and for various use:] It were impossible, in the short limits of a note, to enumerate the various uses of Sugar; and, indeed, as these are in general so well known, it is needless. A few properties of it, however, wherewith the learned are not commonly acquainted, I shall mention. In some places of the East-Indies, an excellent arrack is made from the Sugar-Cane: And, in South-America, Sugar is used as an antidote against one of the most sudden, as well as fatal poisons in the world. Taken by mouth, pocula morte carent,55 this poison is quite innocent; but the slightest wound made by an arrow, whose point is tinged therewith, proves immediate death; for, by driving all the blood of the body immediately to the heart, it forthwith bursts it.56 The fish and birds killed by these poisoned arrows (in the use of which the Indians are astonishingly expert) are perfectly wholesome to feed on. See Ulloa and De la Condamine’s account of the great river of Amazon.57 It is a vegetable preparation….

VER. 137. cherries,] The tree which produces this wholesome fruit is tall, shady, and of quick growth. Its Indian name is Acajou; hence corruptly called Cashew58 by

the English. The fruit has no resemblance to a cherry, either in shape or size; and bears, at its lower extremity, a nut (which the Spaniards name Anacardo, and physicians Anacardium) that resembles a large kidney-bean. Its kernel is as grateful as an almond, and more easy of digestion. Between its rhinds59 is contained a highly caustic oil; which, being held to a candle, emits bright salient sparkles, in which the American fortune-tellers pretended they saw spirits who gave answers to whatever questions were put to them by their ignorant followers. This oil is used as a cosmetic by the ladies, to remove freckles and sun-burning; but the pain they necessarily suffer makes its use not very frequent. This tree also produces a gum not inferior to Gum-Arabic;60 and its bark is an approved astringent. The juice of the cherry stains exceedingly. The long citron, or amber-coloured, is the best. The cashew-nuts, when unripe, are of a green colour; but, ripe, they assume that of a pale olive. This tree bears fruit but once a year….

-

A term of Grainger’s invention. Building on his opening claim that the Caribbean would transform the face of poetry, Grainger simultaneously leans on a traditional mode (the georgic) and imagines a new form for it (West-India). It is worth considering what specifically about this poem makes it West Indian or Caribbean. ↩︎

-

Grainger’s mention of indigenous remedies refers in part to the botanical knowledge possessed by indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, but it also refers to the local knowledge that African and European transplants to the Caribbean developed as they learned about the new environment. In particular, Grainger uses the poem to display his knowledge of husbandry, medicine, and natural history. We have tried in our notes to identify the origins of the plants named by Grainger. While some of these plants do originate from the Caribbean and the Americas, others come from Africa, Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world. In many cases, these foreign plants were brought to the Caribbean purposefully, as individuals sought to transform their new homes by importing crops and commodities that could help them survive and profit. ↩︎

-

Born in Scotland, Grainger was trained as a physician in Edinburgh, but he had significant literary ambitions dating back at least to the mid-1750s, when he settled in London. The sentence that closes his preface has long fascinated critics because it suggests a certain ambivalence about the aims and the form of the poem. Certainly, Grainger was aware that the inclusion of local knowledge and the proliferation of footnotes were unusual, and he anticipated criticism of his choices. ↩︎

-

Sabbaca refers to avocado (Persea americana), which probably originated in Central America. It then spread to the Caribbean in the aftermath of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Avocado was an important part of the diets of the enslaved who had access to it: they harvested it from woodlands, versus growing it in provision grounds or gardens (Higman 158-160). ↩︎

-

Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Giral (1716-1795) was a colonel and naval officer of the Spanish navy, as well as an explorer and scientist. He participated in a geodesic mission to the equator in Peru to measure the earth’s true shape. After the mission was completed, Ulloa co-authored with Jorge Juan the Relación histórica del viage a la América meridional (1748). ↩︎

-

There are multiple varieties of avocado. The one that Grainger identifies as bearing a green fruit may be Persea americana var. americana, also known as the West Indian avocado. The one that Grainger identifies as growing chiefly in Mexico may be Persea americana var. drymifolia, also known as the Mexican avocado. ↩︎

-

Of the nature of butter; buttery. ↩︎

-

Hans Sloane (1660-1753) was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector who traveled to Jamaica in 1687 with Christopher Monck, second duke of Albemarle and newly appointed governor of Jamaica. During his stay in Jamaica, Sloane amassed an extensive collection of natural specimens, including plants, that later served as the basis for his natural history, A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica (1707, 1725). Sloane also succeeded Isaac Newton as president of the Royal Society in 1727. Upon his death, he bequeathed his extensive collections, which he had made considerable additions to after returning from Jamaica, to the British nation. These served as the founding collections of the British Museum, the British Library, and the Natural History Museum in London. ↩︎

-

This is a pear known today as the jargonelle pear (Pyrus communis ‘Jargonelle’). It is one of the oldest pears in cultivation. ↩︎

-

Anise wood. The leaves of some varieties of avocado give off a scent of anise when crushed. ↩︎

-

The island of St. Christopher was known as Liamuiga by the indigenous Caribs who lived there. Columbus claimed it on behalf of Spain in 1493, and it was partitioned between the French and the English in the early seventeenth century, at which time it was primarily a tobacco colony. While the two countries exchanged control of the island several times during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was firmly under British control when Grainger left England in 1759 during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Grainger uses “St. Christopher,” “Liamuiga,” and “St. Kitts” interchangeably in the poem, but we have chosen to use “St. Kitts” on this site. St. Kitts has been part of the nation of St. Kitts and Nevis (also known as the Federation of St. Christopher and Nevis) since it gained independence from Great Britain in 1983. ↩︎

-

John of Gaunt describes England as “A precious stone, set in the silver sea” in Shakespeare’s Richard II (2.1.46). ↩︎

-

Seventeenth north latitude, one of the coordinates for St. Kitts. ↩︎

-

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), a Genoese-born explorer. The purpose of his famed 1492 voyage was to discover a western route to Asia. He set sight on the island of Guanahani (in the Bahamas) on October 12. Columbus completed four voyages to the Americas during his lifetime. ↩︎

-

Grainger may be referring to the legend that St. Christopher, whose name means “Christ carrier,” once carried Jesus in the form of a child across a river. Mount Misery was the name used by Europeans for the main volcanic mountain on St. Kitts. It was renamed Mt. Liamuiga when St. Kitts and Nevis became independent. ↩︎

-

Grainger is referring to Thomas Templeman’s A New Survey of the Globe: Or, an Accurate Mensuration of all the…Countries…in the World (1729). ↩︎

-

A dark brown, unrefined sugar that was typically the end product of the sugar-making process in the Caribbean. Often described as unrefined since it was usually processed further in Europe and lightened in color before being sold to consumers. ↩︎

-

Grainger refers here to enslaved persons running away from plantations and taking advantage of the rough terrain near Mt. Liamuiga to evade re-capture. A solfaterre is a volcano. ↩︎

-

Tobacco, indigo, coffee, and cotton were major agricultural commodities in the eighteenth-century Caribbean. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) is native to the Americas. Indigo (genus Indigofera) is found in tropical regions throughout the world. Various species are used in the production of blue dye. Commercial cotton (genus Gossypium) is produced from several different species, some of which are native to the Old World and others of which are native to the New World. Coffee is made from the roasted seeds of the genus Coffea. Coffea arabica, the most widely cultivated species, is native to northeast tropical Africa. ↩︎

-

King James was King James II of England and Ireland and James VII of Scotland (1633–1701). Son of Charles I, James II became king of England after the death of his brother, Charles II. He was the last Roman Catholic king of England and abdicated in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution. ↩︎

-

Also Treaty of Rijswijk, signed in 1697 and named after the Dutch city in which it was signed. The treaty ended the Nine Years’ War (1689-1697), in which Louis XIV’s France faced a grand coalition of England, the Holy Roman Empire, the Dutch, and Spain. The treaty confirmed the effective disappearance of Spain as a maritime and continental power. ↩︎

-

Martinico. Spanish name for the island of Martinique, the northernmost of the Windward Islands. Now an overseas department of France. ↩︎

-

The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) was part of the general settlement ending the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714). The treaty confirmed Philip V as King of Spain but required him to abandon his claim to the French throne. Additional provisions included the Spanish forfeiture of Gibraltar and Minorca to the British and the French forfeiture of claims to Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Prince Rupert’s Land in northern Canada. The French also had to cede the formerly partitioned St. Kitts entirely to the British. The British received the Asiento as well, a monopoly contract to supply the Spanish Americas with enslaved Africans. ↩︎

-

Ficus citrifolia, also known as the wild banyan tree. It is the national tree of Barbados, and its native range includes Florida and the tropical Americas. ↩︎

-

Quintus Curtius Rufus (1st century CE), Roman historian and author of Histories of Alexander the Great. ↩︎

-

John Milton (1606-1674) was an English poet and polemicist. Especially known for Paradise Lost (1667) and Samson Agonistes (1671). Grainger quotes here from Paradise Lost (9.1101-1110). ↩︎

-

Malabar is a region on the southwest coast of India (modern Kerala). Decan refers to the Deccan plateau, immediately to the east of Kerala. ↩︎

-

Grainger means that the Spanish left livestock to breed in Barbados so that the island would supply them with provisions on future trips. ↩︎

-

Birds of the family Trochilidae. ↩︎

-

George Edwards (1694-1773), English artist and ornithologist. Author of A Natural History of Uncommon Birds (1743-1751). ↩︎

-

Cassava (Manihot esculenta), also known as manioc, yuca, and bitter cassava, which was domesticated in South America thousands of years ago and then brought to the Caribbean islands by Amerindians. One of the most important food sources for Amerindians during the precolonial era; subsequently adopted by Africans and Europeans in the Caribbean as well. Nevertheless, cassava is highly poisonous: its roots, which are the parts of the plant that are prepared for consumption, contain cyanide, and the raw root is poisonous to human beings. Cassava has advantages that offset its toxic nature, however: it can grow in poor soils and conditions, one planting produces several harvests, and the roots can be stored in the ground for a long time without spoiling. The root’s poison also can be neutralized by proper processing: Amerindians and other early Caribbean consumers usually processed cassava root by grating it and then pressing the poisonous juice out of it to make a flour, which could be eaten as a porridge or turned into various cakes or breads (Higman 61-69). ↩︎

-

Cultivated varieties of cassava are classed into two groups: sweet and bitter. Sweet cassava is not poisonous and can be eaten without the processing that bitter cassava requires. Although it is more dangerous to eat, bitter cassava historically has been cultivated more than sweet cassava, perhaps because it has a higher yield and because it makes a better flour (Higman 62). ↩︎

-

There are reports from the colonial Caribbean of cassava being made into a drink called perino (Higman 69). ↩︎

-

Jean Antoine Bruletout de Préfontaine’s Maison rustique, à l’usage des habitans de la partie de la France équinoxiale connue sous le nom de Cayenne (1763) also mentions a kind of cassava called Baccacoua that is consumed only by the Amerindians in Cayenne, a French colony on the northeastern coast of South America (now the name of the capital of French Guiana). ↩︎

-

The soursop (Annona muricata) is a fruit of tropical American origin. ↩︎

-

The custard apple (Annona reticulata) is the fruit of a tree whose native range is Mexico to northeastern Venezuela. The star apple (Chrysophyllum cainito) is the fruit of a tree native to the Greater Antilles (Higman 202). Sugar apple (Annona squamosa), also known as sweetsop, is the fruit of a tree native to lowland Central America. ↩︎

-

A grove of cacao trees. The cacao tree (Theobroma cacao) is the source of chocolate, which is made from the seeds of the cacao tree. Cacao is native to Central and South America and was first cultivated by Amerindians thousands of years ago. Europeans first encountered cacao in Mexico, where the Aztecs placed a high value on it: cacao was prepared into chocolate drinks that were consumed by the Aztec elite, as well as during religious rituals, and cacao seeds were used as currency and tribute. Cacao was first brought to the Caribbean by Spaniards, who established plantations to supply Europe with chocolate. Although some Europeans initially found the taste of chocolate off-putting (the Aztecs did not add sugar to their chocolate), it was being consumed in Europe in significant quantities by the seventeenth century. ↩︎

-

The Aztecs flavored their chocolate with vanilla (Vanilla planifolia), which is native to Mexico and Belize, as well as other spices, including chili peppers (genus Capsicum), which have a native range that includes Mexico and the tropical Americas. Grainger was not necessarily thinking of the spiciness of ingredients when he referred to them as “hot,” however. He may instead have meant that vanilla, pepper, and other spices were hot in a humoral sense: according to humoral theories of health, all foods possessed elemental qualities that reflected some combination of heat, moisture, coldness, or dryness. These foods could, in turn, impart those qualities to those who ate them and thus needed to be regulated to complement the humoral properties of consumers’ bodies, which also were hot, cold, moist, or dry. ↩︎

-

The olive tree (Olea europaea) is widely distributed across the Mediterranean region, Africa, and Asia and has been cultivated in the Mediterranean for over five thousand years. ↩︎

-

Gliricidia sepium. Its native range includes Mexico, Central America, and South America, and it is used as a shade tree for cacao and other plants. ↩︎

-

Cacao trees produce large pods that contain the cacao seeds, also known as cacao beans or nuts. ↩︎

-

The cucumber (Cucumis sativus) has a native range extending from Himalaya to northern Thailand. ↩︎

-

There are three main varieties of cacao used in commercial chocolate production today: the Forastero, the Trinitario, and the Criollo. The Criollo is the most prized variety and probably the one Grainger was referencing, since it is still grown in Venezuela (Caracas is the capital of Venezuela). ↩︎

-

“Cacao” is derived from the Nahuatl word cacahuatl. The scientific name for cacao, Theobroma cacao, also includes a Greek term that translates to “food of the gods.” ↩︎

-

The coconut palm (Cocos nucifera), which is native to coastal areas of Melanesia and Southeast Asia, has great powers of natural disperal since its nuts (the coconuts) can survive up to 120 days in seawater. Nevertheless, it is believed that Europeans introduced the coconut palm to the Caribbean in the sixteenth century. ↩︎

-

A theoretical climatic zone lying between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer; the tropics. The ancients believed that the torrid zone was uninhabitable. While the colonization of the Caribbean proved otherwise, many continued to believe that the tropics could induce what they called degeneration or the degradation of bodies and faculties. Furthermore, the fear of degeneration was intertwined with theories of geographic and racial difference, since it was usually argued that New World forms of nature, including human beings, were inferior to Old World ones and that Europeans hence would become inferior by inhabiting the Americas. ↩︎

-

Also arak, an alcohol distilled from the fermented sap of the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera). ↩︎

-

The Orinoco river, which passes through modern Colombia and Venezuala. ↩︎

-

Chile. ↩︎

-

The Maldives archipelago, which is in the Indian Ocean. Now the Republic of Maldives. ↩︎

-

Possibly jaggery, a coarse, dark brown sugar made by evaporation from the sap of various kinds of palm. ↩︎

-

Distilled liquor. ↩︎

-

The coca plant, the source of cocaine. Two species of coca are now in cultivation: Erythroxylum coca, whose native range is western South America, and Erythroxylum novogranatense, whose native range is Colombia to northwestern Venezuela and Peru. ↩︎

-

Havana, the capital of Cuba, which the British took in 1762 during the Seven Years’ War. ↩︎

-

“The cups contain no death.” ↩︎

-

The poison Grainger refers to is curare, an extract obtained from the bark of South American trees of the genera Strychnos and Chondrodendron that relaxes and paralyzes voluntary muscles. Curare’s use as an arrow poison was reported by Europeans from their earliest encounters with Amerindians in South America. ↩︎

-

Charles-Marie de La Condamine (1701-1774), a French scientist, participated with Ulloa in a geodesic mission to the equator in Peru to measure the earth’s true shape. After the mission was completed, La Condamine published the Relation abrégée d’un voyage fait dans l’intérieur de l’Amérique méridionale (1745) and Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi a l’équateur (1751). ↩︎

-

The cashew or cashewnut tree (Anacardium occidentale). Its native range is Trinidad to tropical South America. As Grainger and others note, the fruit of the cashew tree is caustic, and it was supposedly used by women as a chemical peel to remove freckles (Riddell 82-83). ↩︎

-

The “Errata” list at the end of The Sugar-Cane indicates that “rhinds” should read “rinds.” ↩︎

-

Edible sap of some trees in the genus Acacia. Used as a binder or stabilizer in foods and medicines. ↩︎