Provision Grounds

Because Book IV represents Grainger’s attempt to deal with the subject of enslaved labor, it contains many passages that purport to be concerned for the welfare of the enslaved. For example, in line 423, Grainger identifies his poetic muse as a “soft daughter of humanity” and then calls on his imagined planter readers to treat the enslaved kindly, promising that such an approach will encourage the worker “By day, by night, to labour for his lord” (427). Grainger was an ameliorationist, meaning that he believed better treatment of the enslaved could lead to increased productivity. Ameliorationists also were in favor of maintaining the system of slavery and believed that it simply needed to be reformed.

In the passages selected below, Grainger specifically appeals to planters to provide their enslaved laborers with greater quantitites of rations or provisions. It was common practice for planters to skimp on providing their workers with enough food, since they wanted to economize on costs and thereby increase their profits. Also, planters tended to rely on imported provisions from Europe and North America for rationing. Although these provisions had to be paid for, planters did not want to take up any land that could be used for sugar cultivation by growing provision crops.

For most of the lines dedicated to provisioning, then, Grainger ends up describing not the actions that planters took to provide food for their plantations but the provision grounds of the enslaved. Provision grounds were plots of land unsuitable for cane cultivation that were allotted to the enslaved. The enslaved were then allowed–or required–to cultivate these provision grounds with subsistence crops to supplement planter-provided rations. Of course, since they had to continue cultivating cane and doing other work for their enslavers, they were expected to cultivate their provision grounds only during their “spare” time, including their days of “rest.” The lands allotted for provision grounds also were difficult to cultivate, since they were typically located a long distance from the cane fields and habitations of the enslaved. Additionally, they were generally located on rocky, mountainous plots with poor-quality soil. How effective provision ground cultivation was at enabling their cultivators to maintain adequate sources of nutrition is, as a result, debatable: studies of survival rates across colonies have suggested that individuals dependent on provision grounds did not enjoy, on average, better health or longer lifespans than those dependent primarily on imported rations.

Still, the provision grounds did offer their cultivators some degrees of autonomy. They could, for example, exercise more choice over what they ate since they were growing their own food. Note in the passages below how many of the specific plants that Grainger mentions as growing in the provision grounds had arrived in the Americas from Africa. While it is unlikely that the enslaved themselves were able to carry these plants from Africa–captives were not allowed any possessions on slave ships–slave ships often stocked African crops to feed their captives during the passage across the Atlantic, and the crops them became established in the Americas, where the enslaved continued to cultivate what they had been used to cultivating in Africa. Also note how many of the plants and foodstuffs mentioned by Grainger are plants indigenous to the Americas and long cultivated by Amerindians. The prevalence of these crops, which were often hardy, high-yield staples, suggests that newly arrived Africans engaged in significant exchanges of knowledge with Amerindians and that this knowledge sharing continued to have long-lasting effects well beyond the initial period of contact.

Provision grounds can, in fact, be read as records of the resourcefulness and creativity of their cultivators, who dealt with the poor quality of the lands they were given by learning how to grow plants that others shunned. Although certain plants may have been designated weeds by colonists, the enslaved realized that proper preparation and cooking methods could turn these so-called weeds into valuable sources of nutrition. The dishes prepared by the enslaved in the Caribbean even infiltrated colonists’ cuisine, which became increasingly indebted to Afro-Caribbean ingredients and influences. Colonists also became reliant in certain colonies like Jamaica on enslaved cultivators for most of their own local foodstuffs. Because the cost of importing food was high, they purchased produce from the enslaved, who were allowed to use and accumulate currency. Although it was rare for cultivators to make enough money to purchase their freedom, they were nevertheless able to make money and profit from what is now known as the internal marketing system. The internal marketing system, in turn, has been recognized as providing a crucial foundation for the counter-plantation system that emerged in post-emancipation Caribbean colonies. Those who participated in the counter-plantation system eschewed the model of industrial agriculture represented by the plantation and instead focused on small-scale farming, whether for subsistence or trade and export.

As you read the below passages, think about how Grainger describes the provision grounds, and pay particular attention to what was growing in them. It is also worth thinking about the end of the passages treating the provision grounds: why does Grainger turn suddenly to a vision of fugitives coming to raid the provision grounds? What threat might he really fear?

Note: B. W. Higman’s Jamaican Food was an invaluable source of information for many of the notes about specific plants mentioned in this section of the poem. Also see Judith A. Carney and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff’s In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World for more information about Afro-Caribbean provision grounds and cultivation practices.

—Julie Chun Kim

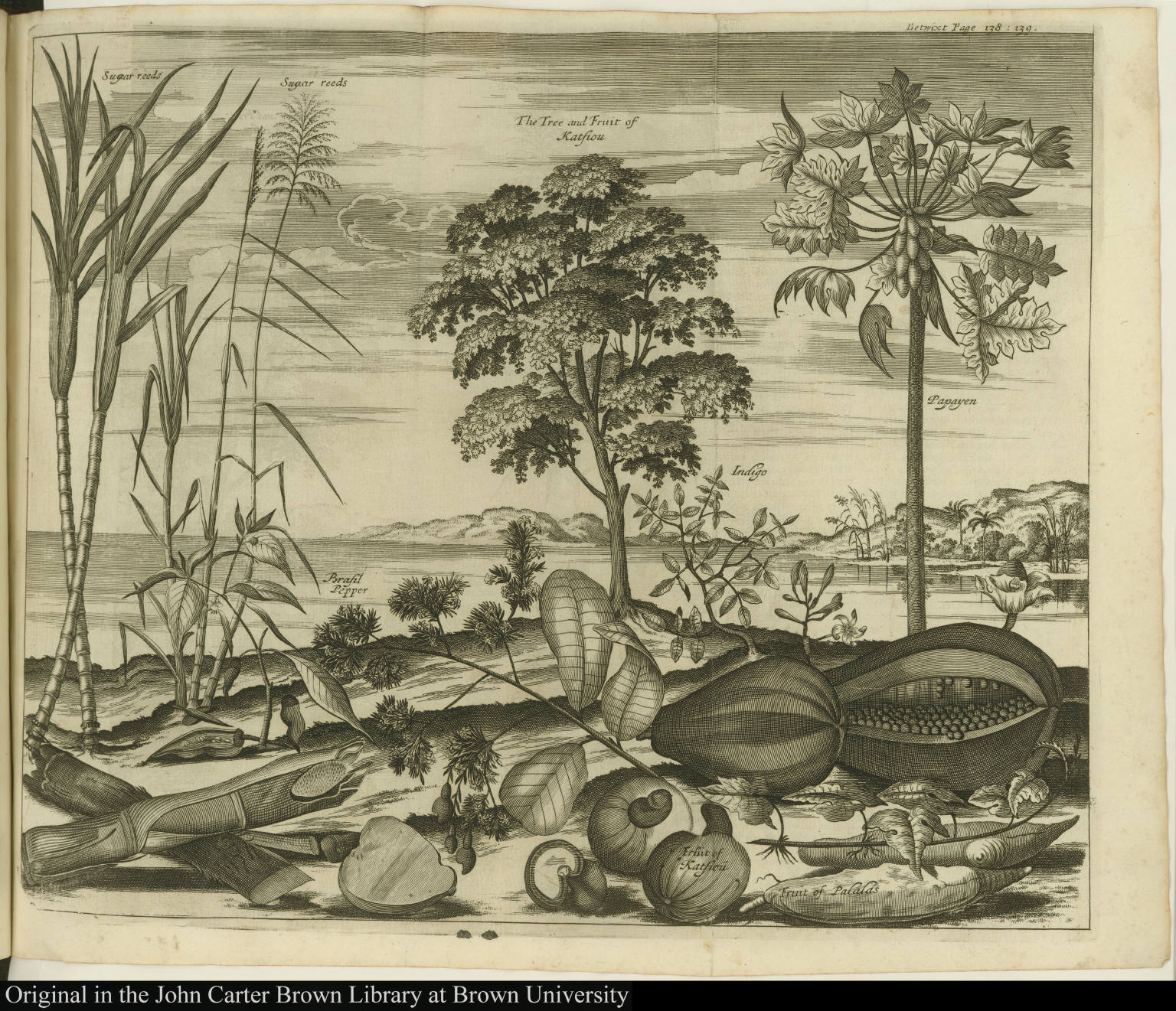

Various plants and fruits from Brazil, including cashews and papayas, engraved plate from A Collection of Voyages and Travels, London, 1704, v. 2, following p. 138.

Various plants and fruits from Brazil, including cashews and papayas, engraved plate from A Collection of Voyages and Travels, London, 1704, v. 2, following p. 138.

- HOWE’ER insensate some may deem their slaves,

- Nor ‘bove the bestial rank; far other thoughts

- The muse, soft daughter of humanity!

- Will ever entertain.—The Ethiop knows,

- The Ethiop feels, when treated like a man;1 [425]

- Nor grudges, should necessity compell,

-

By day, by night, to labour for his lord.

- NOT less inhuman, than unthrifty those;

- Who, half the year’s rotation round the sun,

- Deny subsistence to their labouring slaves.2 [430]

- But would’st thou see thy negroe-train encrease,

- Free from disorders; and thine acres clad

- With groves of sugar: every week dispense

- Or English beans, or Carolinian rice;3

- Iërne’s beef, or Pensilvanian flour;4 [435]

- Newfoundland cod,5 or herrings from the main

-

That howls tempestuous round the Scotian isles!

- YET some there are so lazily inclin’d,

- And so neglectful of their food, that thou,

- Would’st thou preserve them from the jaws of death; [440]

- Daily, their wholesome viands must prepare:

- With these let all the young, and childless old,

- And all the morbid share;—so heaven will bless,

-

With manifold encrease, thy costly care.

- SUFFICE not this; to every slave assign [445]

- Some mountain-ground: or, if waste broken land

- To thee belong, that broken land divide.

- This let them cultivate, one day, each week;6

- And there raise yams,7 and there cassada’s root:8

- From a good daemon’s staff cassada sprang, [450]

- Tradition says, and Caribbees believe;

- Which into three the white-rob’d genius broke,

- And bade them plant, their hunger to repel.

- There let angola’s bloomy bush9 supply

- For many a year, with wholesome pulse their board. [455]

- There let the bonavist,10 his fringed pods

VER. 449. cassada] To an antient Carribean, bemoaning the savage uncomfortable life of his countrymen, a deity clad in white apparel appeared, and told him, he would have come sooner to have taught him the ways of civil life, had he been addressed before. He then showed him sharp-cutting stones to fell trees and build houses; and bade him cover them with the palm leaves. Then he broke his staff in three; which, being planted, soon after produced cassada. See Ogilvy’s America.11

VER. 454. angola] This is called Pidgeon-pea, and grows on a sturdy shrub, that will last for years. It is justly reckoned among the most wholesome legumens. The juice of the leaves, dropt into the eye, will remove incipient films. The botanic name is Cytisus.

VER. 456. bonavist] This is the Spanish name of a plant, which produces an excellent bean. It is a parasitical plant. There are five sorts of bonavist, the green, the white, the

- Throw liberal o’er the prop; while ochra12 bears

- Aloft his slimy pulp, and help disdains.

- There let potatos mantle o’er the ground;

- Sweet as the cane-juice is the root they bear.13 [460]

- There too let eddas14 spring in order meet,

- With Indian cale, and foodful calaloo:15

- While mint, thyme, balm,16 and Europe’s coyer herbs,

- Shoot gladsome forth, nor reprobate the clime.

moon-shine, the small or common; and, lastly, the black and red. The flowers of all are white and papilionaceous;17 except the last, whose blossoms are purple. They commonly bear in six weeks. Their pulse is wholesome, though somewhat flatulent; especially those from the black and red. The pods are flattish, two or three inches long; and contain from three to five seeds in partitional cells.

VER. 457. Ochra] Or Ockro. This shrub, which will last for years, produces a not less agreeable, than wholesome pod. It bears all the year round. Being of a slimy and balsamic nature, it becomes a truly medicinal aliment in dysenteric complaints. It is of the Malva species. It rises to about four or five feet high, bearing, on and near the summit, many yellow flowers; succeeded by green, conic, fleshy pods, channelled into several grooves. There are as many cells filled with small round seeds, as there are channels.

VER. 459. potatos] I cannot positively say, whether these vines are of Indian original or not; but as in their fructification, they differ from potatos at home, they probably are not European. They are sweet. There are four kinds, the red, the white, the long, and round: The juice of each may be made into a pleasant cool drink; and, being distilled, yield an excellent spirit.18

VER. 461. eddas] See notes on Book I. The French call this plant Tayove. It produces eatable roots every four months, for one year only.

VER. 462. Indian cale] This green, which is a native of the New World, equals any of the greens in the Old.

VER. 462. calaloo] Another species of Indian pot-herb, no less wholesome than the preceding. These, with mezamby,19 and the Jamaica prickle-weed,20 yield to no esculent21 plants in Europe. This is an Indian name.

- THIS tract secure, with hedges or of limes, [465]

- Or bushy citrons, or the shapely tree

- That glows at once with aromatic blooms,

- And golden fruit mature.22 To these be join’d,

- In comely neighbourhood, the cotton shrub;

- In this delicious clime the cotton bursts [470]

- On rocky soils.23—The coffee also plant;

- White as the skin of Albion’s lovely fair,

- Are the thick snowy fragrant blooms it boasts:24

- Nor wilt thou, cocô,25 thy rich pods refuse;

- Tho’ years, and heat, and moisture they require, [475]

- Ere the stone grind them to the food of health.26

- Of thee, perhaps, and of thy various sorts,

- And that kind sheltering tree, thy mother nam’d,

- With crimson flowerets prodigally grac’d;27

- In future times, the enraptur’d muse may sing: [480]

-

If public favour crown her present lay.

- BUT let some antient, faithful slave erect

- His sheltered mansion near; and with his dog,

- His loaded gun, and cutlass, guard the whole:

- Else negro-fugitives, who skulk ‘mid rocks [485]

VER. 466. the shapely tree] The orange tree.

VER. 478. thy mother nam’d] See Book I p. 43.

- And shrubby wilds, in bands will soon destroy

- Thy labourer’s honest wealth; their loss and yours….

-

Ethiop and Ethiopia were sometimes used by the Greeks and Romans to refer to a specific people and region of Africa, but Ethiop was used to designate a generically black African as well. Ethiopians also were referenced in a classical proverb about “washing the Ethiopian” or turning black skin white. The proverb and subsequent versions, which were widely circulated in the early modern period and eighteenth century, framed the task as impossible and hence were used in justifications of racial difference based on skin color. ↩︎

-

Grainger addresses the fact that, in order to economize on costs, planters did not provide enslaved laborers with enough food. Likewise, they wanted to maximize the amount of fertile land was dedicated to sugarcane and therefore did not engage in the large-scale cultivation of provision crops. In addition to working full-time to produce sugar and other commodity crops, then, enslaved laborers were frequently required to cultivate provision grounds or gardens to supplement their diets. The lands allotted for provision grounds were generally rocky, mountainous plots with poor soil. ↩︎

-

Beans or peas, as they were often called in the Caribbean, were a major source of nutrition for the enslaved. English beans are also known as fava, broad, or horse beans (Vicia faba), which originated in Western Asia thousands of years ago and spread from there to Central Asia, Europe, and Africa. They were sometimes sent from England to the Caribbean to serve as provisions. They also formed part of the provisions of slave ships. The horse bean was not as central to the diets of the enslaved as other bean species, however, many of which were cultivated by the enslaved themselves. Rice also did not make up a major part of the diets of the enslaved in the Caribbean, but South Carolina was the major Atlantic exporter of the rice species known as Oryza sativa, which originated in Asia. There is also a species of rice indigenous to Africa known as Oryza glaberrima. Enslaved persons may occasionally have grown both Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima in their provision grounds and gardens. ↩︎

-

Iërne is a term for Ireland, which supplied Caribbean plantations with salted beef and other provisions. Beef also came from the North American colonies, as did flour. ↩︎

-

The waters off the coast of Newfoundland in the North Atlantic constituted one of the major fisheries of the world for the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in the eighteenth century. Planters imported cod for enslaved laborers, who needed protein, but they imported what came to be known as “West India cod,” which was salted cod of the poorest quality. ↩︎

-

Enslaved laborers were generally required to go to their provision grounds one day per week to tend them. In certain colonies, however, an internal marketing system gradually emerged that may have encouraged some to spend extra time cultivating their provision grounds. For instance, in Jamaica, those who participated in the system were able to sell or trade their provisions for other goods and currency. They were also able to supplement the inadequate diet provided to them by planters, although those individuals who cultivated provision grounds did not enjoy, on average, better health or longer lifespans than those dependent primarily on imported rations. Still, the provision grounds did offer their cultivators some control over what they ate, as they were responsible for choosing what plants to cultivate, and, in limited cases, they also offered some degree of economic autonomy. They also laid the foundation for agricultural production in the British Caribbean in the years following emancipation. Eschewing the model of industrial agriculture represented by the plantation, the newly freed turned instead to small-scale farming. ↩︎

-

One of many species of tubers within the Dioscorea genus. One of the most important food crops for enslaved persons in the Caribbean. There are several reasons yams became important to Afro-Caribbean diets: yam crop yields are high, yams are easily stored, and they can be prepared in several different ways. Just as crucially, yams formed a part of West African diets long before the commencement of the slave trade. As a result, slave traders often shipped large quantities of yams on trans-Atlantic voyages to feed the people on board, and yams accompanied Africans to the Americas, where they were able to continue cultivating them. Although there is one South American species of yam (Dioscorea trifida) that was transplanted to the Caribbean by Amerindians and consumed by subsequent inhabitants of the region, more important species to the diets of the enslaved were Dioscorea cayenensis, which is native to West Africa, and Dioscorea alata, which is native to Southeast Asia but had been introduced to the west coast of Africa by the Portuguese and Spanish by the sixteenth century (Higman 72-81). ↩︎

-

Cassava (Manihot esculenta), also known as manioc, yuca, and bitter cassava, was domesticated in South America thousands of years ago and then brought to the Caribbean islands by Amerindians. It was one of the most important food sources for Amerindians during the precolonial era and subsequently adopted by Africans and Europeans in the Caribbean as well, although it was not as important a food source as the yam. Nevertheless, it still appeared in provision grounds because it is an easy crop to cultivate: it can grow in poor soils and conditions, one planting produces several harvests, and the roots can be stored in the ground for a long time without spoiling. These advantages offset cassava’s toxic nature: its roots, which are the parts of the plant prepared for consumption, contain cyanide, and the raw roots are poisonous to human beings. The poison can be neutralized by proper processing, however: Amerindians and other early Caribbean consumers usually prepared cassava root by grating it and then pressing the poisonous juice out of it to make a flour, which could be eaten as a porridge or turned into various cakes or breads (Higman 61-69). ↩︎

-

Refers to the pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). Pigeon pea is a drought-resistant crop that has historically been important for small-scale farmers in semi-arid areas. It was commonly grown in the provision grounds or gardens of the enslaved because it could survive without much water or attention. It is native to South Asia and was first domesticated in India. By 2000 BCE, it also was being cultivated in East Africa, from where it was brought to the Americas, most likely as a result of the slave trade. ↩︎

-

A species of bean (Lablab purpureus) whose native range includes the Cape Verde Islands, tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, and India. ↩︎

-

John Ogilby’s America: being the latest, and most accurate description of the New World (1671). Ogilby (1600-1676) was a Scottish publisher and geographer. ↩︎

-

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) is probably native to Africa and was one of the most commonly cultivated plants in the provision grounds and gardens of the enslaved. It possesses a glutinous or slimy pulp that was used as a thickener in stews called pepper pots, one of the most popular dishes in the colonial Caribbean (Higman 174-175). ↩︎

-

Grainger refers to sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas), which probably originated in Central America or northwestern South America. ↩︎

-

Edda or eddo commonly referred to taro (Colocasia esculenta). It is also, however, sometimes referred to as yautia (Xanthosoma sagittifolium). Both plants produce roots that were commonly consumed by the enslaved because they were easy to cultivate and had a high yield. Colocasia esculenta originated in southeastern or southern Central Asia but was being cultivated in Africa by 100 CE. From there, it was brought to the Americas on slave ships, which stocked it as food. Xanthosoma sagittifolium has a native range extending from Costa Rica to tropical South America (Higman 82-86). ↩︎

-

The term “Indian cale” also can refer to the species Colocasia esculenta and Xanthosoma sagittifolium. Since the seventeenth century, “callaloo” has been used to refer to several different plants. Today, callaloo usually refers to Amaranthus viridis, a plant whose native range is the tropical Americas. What the various plants labeled callaloo had in common was the ability of their leaves to serve as edible greens. They are also weedy plants that can survive in a wide range of environments, including wastelands. They formed an important part of the diets of the enslaved, probably because they were a hardy and reliable source of food (Higman 100-107). ↩︎

-

Mint refers to plants of the genus Mentha, distributed around the world. Thyme refers to plants of the genus Thymus, whose native range extends from Greenland and temperate and subtropical Eurasia to northeastern tropical Africa. Balm is the name of various aromatic plants, particularly those of the genera Melissa and Melittis. ↩︎

-

Butterfly-shaped. ↩︎

-

Mobby or mobbie, an alcoholic drink made from the sweet potato. The origin of the drink’s name is Carib. ↩︎

-

Gilmore identifies mezamby as probably Cleome gynandra, a plant whose native range is the tropical and subtropical Old World. ↩︎

-

Might refer to Amaranthus spinosus, a plant sometimes known as prickly callaloo. Its native range is Mexico and the tropical Americas. ↩︎

-

Suitable for food, edible. ↩︎

-

Grainger is describing members of the genus Citrus. Citrus fruits originated in Southeast Asia and spread from there to the Mediterranean and Spain. Columbus brought sour oranges (Citrus aurantium), sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis), limes (Citrus aurantifolia), and citrons (Citrus medica) to the Caribbean. He probably also carried lemons (Citrus limon) (Higman 175). ↩︎

-

Commercial cotton (genus Gossypium) is produced from several different species, some of which are native to the Old World and others of which are native to the New World. ↩︎

-

Coffee is made from the roasted seeds of the genus Coffea. Coffea arabica, the most widely cultivated species, is native to northeast tropical Africa. ↩︎

-

Cacao. The cacao tree (Theobroma cacao) is the source of chocolate, which is made from the seeds of the cacao tree. Cacao is native to Central and South America and was first cultivated by Amerindians thousands of years ago. Europeans first encountered cacao in Mexico, where the Aztecs placed a high value on it: cacao was prepared into chocolate drinks that were consumed by the Aztec elite, as well as during religious rituals, and cacao seeds were used as currency and tribute. Cacao was first brought to the Caribbean by Spaniards, who established plantations to supply Europe with chocolate. Although some Europeans initially found the taste of chocolate off-putting (the Aztecs did not add sugar to their chocolate), it was being consumed in Europe in significant quantities by the seventeenth century. ↩︎

-

Cacao seeds are ground up to produce chocolate, which was branded as early as the seventeenth century as a kind of miracle food that would give its consumers health and strength. For instance, see the title of Henry Stubbe’s 1662 treatise on chocolate, entitled The Indian Nectar, which portrayed chocolate not only as a health food but also as an aphrodisiac. There were also reports from seventeenth-century Jamaica that sailors and others who had to perform hard labor consumed it regularly. It is possible that maroons living in the mountains of Jamaica consumed chocolate as a subsistence food, too (Hughes, The American Physitian 131). ↩︎

-

Grainger is referring to a tree known as Madre de Cacao (Gliricidia sepium). Its native range includes Mexico, Central America, and South America, and it is used as a shade tree for cacao and other plants. ↩︎