Fire

At the beginning of Book III, James Grainger turns to the subject of crop time, the period in which sugarcane was harvested and processed. He portrays the enslaved laborers as happy to begin this work. But at line 55, an interesting thing happens: Grainger pivots to the subject of fire and imagines the cane field being set on fire, perhaps accidentally but also perhaps intentionally. Grainger does not specify whether the fire is caused by “the heavenly bolt” or by the “hand of malice;” nor does he specify who the arsonists might be. However, the fire at midnight might be the result of enslaved resistance on Caribbean plantations, since Grainger hints in Book II, line 123, that enslaved individuals would sometimes set fire to cane fields to avoid working in fields that had been infested with cowitch. In the footnote to this line, Grainger explains that cowitch is an “extraordinary vine [that] should not be permitted to grow in a Cane-piece; for Negroes have been known to fire the Canes, to save themselves from the torture which attends working in grounds where it has abounded.”

This excerpt about the fire at midnight not only shows that plantations were often vulnerable to catastrophes of fire and natural disasters but also hints at the tensions that existed between enslaved laborers and their enslavers. Fire was an essential element to the transformation of sugarcane into sugar: after being crushed, sugarcane had to be boiled to create a syrup, which was then crystallized to produce solid sugar. At the same time, fire could cause disasters and threaten to destroy the entire plantation, especially if it was deployed as a tool of rebellion.

As you read the below excerpts, think about how they depict fire. Does Grainger reach any conclusions about how the fire has started? How does he depict the reactions of enslaved laborers to the fire? How realistic is the portrayal of their reactions, given that they were being forced to work for their enslavers? What does this excerpt reveal about the relationship between natural forces and human beings on the plantation?

Note: Kathleen Donegan’s Seasons of Misery: Catastrophe and Colonial Settlement in Early America discusses the link between fire and rebellion in seventeenth-century Barbados. In Igniting the Caribbean’s Past: Fire in British West Indian History, Bonham C. Richardson points out that “All of the slave uprisings in the eastern Caribbean that preceded emancipation in the 1830s involved the use or planned use of fire” (31).

—Lina Jiang

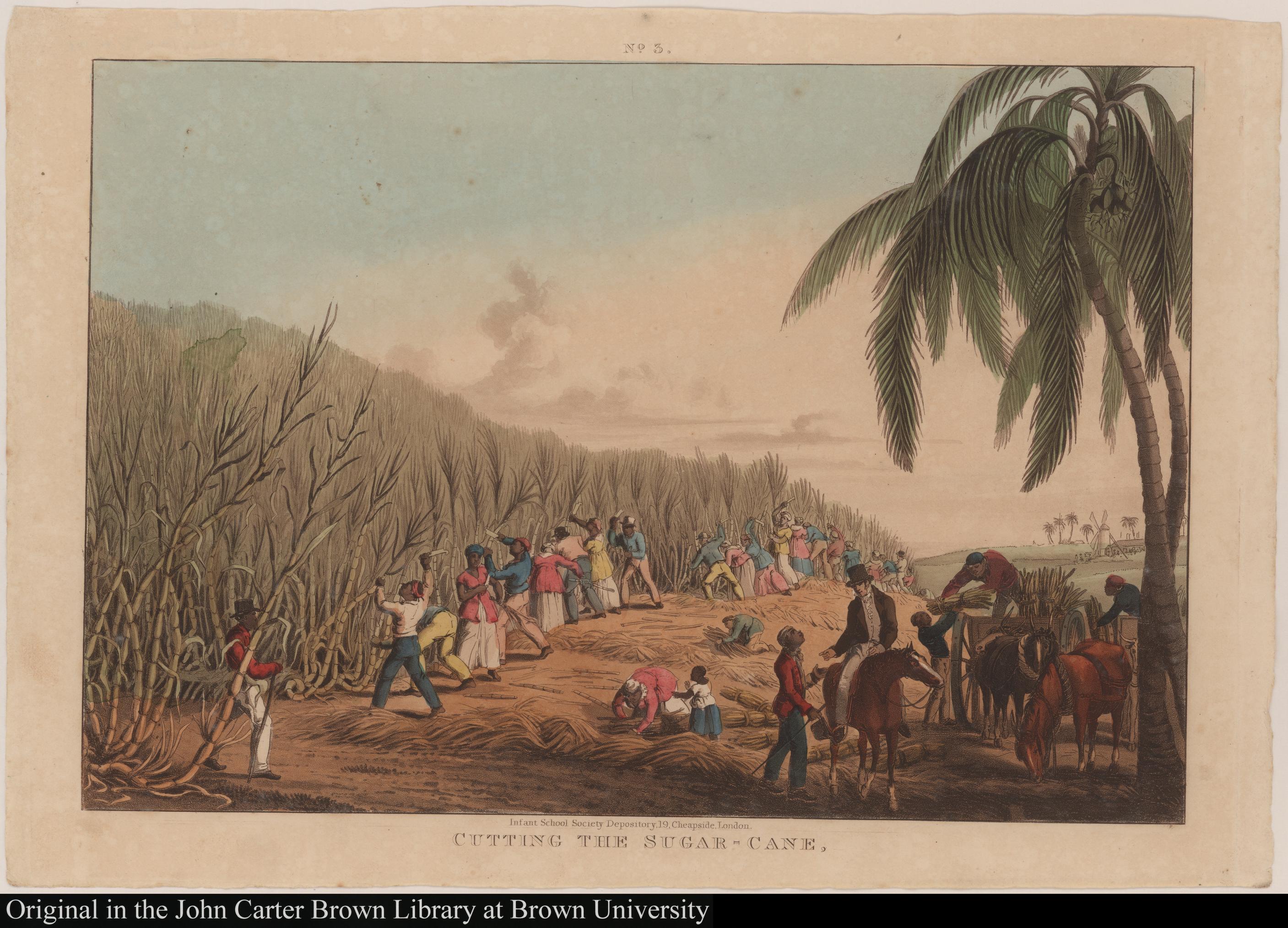

“Cutting the Sugar-Cane,” hand-colored lithograph in untitled folio published by the Ladies’ Society for Promoting the Early Education of Negro Children, London, [ca. 1833-37]. Copied from William Clark, Ten Views of the Island of Antigua, London, 1823, pl. 3.

“Cutting the Sugar-Cane,” hand-colored lithograph in untitled folio published by the Ladies’ Society for Promoting the Early Education of Negro Children, London, [ca. 1833-37]. Copied from William Clark, Ten Views of the Island of Antigua, London, 1823, pl. 3.

- The ripened cane-piece; and, with her, to taste

-

(Delicious draught!) the nectar of the mill! [45]

- THE planter’s labour in a round revolves;1

-

Ends with the year, and with the year begins.

- YE swains, to Heaven bend low in grateful prayer,

- Worship the Almighty; whose kind-fostering hand

- Hath blest your labour, and hath given the cane [50]

-

To rise superior to each menac’d ill.

- NOR less, ye planters, in devotion, sue,

- That nor the heavenly bolt, nor casual spark,

-

Nor hand of malice may the crop destroy.2

- AH me! what numerous, deafning bells, resound? [55]

- What cries of horror startle the dull sleep?

- What gleaming brightness makes, at midnight, day?

- By its portentuous glare, too well I see

- Palaemon’s fate;3 the virtuous, and the wise!

- Where were ye, watches, when the flame burst forth? [60]

- A little care had then the hydra4 quell’d:

- But, now, what clouds of white smoke load the sky!

- How strong, how rapid the combustion pours!

- Aid not, ye winds! with your destroying breath,

-

The spreading vengeance.—They contemn my prayer. [65]

- ROUS’D by the deafning bells, the cries, the blaze;

- From every quarter, in tumultuous bands,

- The Negroes rush; and, ‘mid the crackling flames,

- Plunge, daemon-like! All, all, urge every nerve:

- This way, tear up those Canes; dash the fire out, [70]

- Which sweeps, with serpent-error, o’er the ground.

- There, hew these down; their topmost branches burn:

- And here bid all thy watery engines play;

-

For here the wind the burning deluge drives.

- IN vain.—More wide the blazing torrent rolls; [75]

- More loud it roars, more bright it fires the pole!

- And toward thy mansion, see, it bends its way.

- Haste! far, O far, your infant-throng remove:

- Quick from your stables drag your steeds and mules:

- With well-wet blankets guard your cypress-roofs; [80]

-

And where thy dried Canes in large stacks are pil’d.—

- EFFORTS but serve to irritate the flames:

- Naught but thy ruin can their wrath appease.

- Ah, my Palaemon! what avail’d thy care,

VER. 81. And where thy dried Canes] The Cane-stalks which have been ground, are called Magoss; probably a corruption of the French word Bagasse,5 which signifies the same thing. They make an excellent fewel.

- Oft to prevent the earliest dawn of day, [85]

- And walk thy ranges, at the noon of night?

- What tho’ no ills assail’d thy bunching sprouts,

- And seasons pour’d obedient to thy will:

- All, all must perish; nor shalt thou preserve

-

Wherewith to feed thy little orphan-throng. [90]

- OH, may the Cane-isles know few nights, like this!…

-

Cane cultivation is a year-round affair that nevertheless has distinct rhythms, which arise from the fact that cane can take 15-24 months to mature. ↩︎

-

A reference to arson. Grainger does not specify who the arsonists might be, but this is one of several places where he hints at moments of enslaved resistance on Caribbean plantations. For more on this section of the poem and related passages, see “Fire” on this site. ↩︎

-

Palaemon, also known as Melicertes, was a Greco-Roman sea-god. According to one legend, the goddess Juno killed Melicertes by boiling him in a cauldron; in another, Juno drove Ino, Melicertes’ mother, and Melicertes mad, causing them to throw themselves into the Saronic Gulf, whereupon they were changed into marine deities. Ino became Leucothea, and Melicertes was renamed Palaemon. ↩︎

-

A mythic water snake whose multiple heads could regenerate if severed. Hercules killed the hydra as the second of his twelve Labors. The term also signifies a difficult task. ↩︎

-

Bagasse refers to the crushed sugarcane stalks that are the byproduct of milling cane. Rich in cellulose, bagasse can be used as fuel to boil cane syrup and as cattle feed. ↩︎